Bethesda Fountain at Central Park, NYC

The Victorian (1837–1901) and Edwardian (1901–1910) eras were characterized by rapid industrialization, social reform, and a newfound appreciation for art and design. Nowhere is this shift more evident than in landscaping. During these periods, there was a blossoming interest in gardens, public parks, and thoughtfully curated outdoor spaces, reflecting societal ideals of the time. In the United States, Frederick Law Olmsted, often credited as the father of American landscape architecture, played a transformative role in shaping the way Americans experienced public spaces. His innovative designs and holistic approach left a lasting impact, not only advancing American landscape architecture but also redefining urban living.

The Victorian Landscape Style

Victorian landscapes were opulent and diverse, drawing inspiration from Romanticism and often marked by eclectic combinations of Gothic, Italianate, and Greek Revival influences. This era celebrated elaborate designs, contrasting forms, and the beauty of nature tempered by meticulous human intervention. Victorian gardens often featured winding paths, elaborate flower beds, sculptures, and water features. Fountains, artificial lakes, and even zoos within gardens were common elements, aiming to create spaces that evoked both wonder and relaxation.

One of the defining features of Victorian landscaping was the use of exotic plants and flowers. With expanded trade routes, Victorian gardeners had access to plants from around the world, leading to the popularity of conservatories and greenhouses to protect these delicate specimens. This influx of exotic flora symbolized both wealth and a fascination with the natural world, blending science with aesthetic pleasure.

The gardens at Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC

Edwardian Landscape Style: Simplicity and Order

The Edwardian era brought a shift towards simplicity and order. While Victorian landscapes favored grandeur and variety, Edwardian landscapes leaned towards unity, structure, and natural harmony. Influenced by the Arts and Crafts movement, Edwardian landscapes sought a return to classical ideals, with designs that emphasized proportion, symmetry, and native plants over exotic species.

Hedges, topiaries, and pergolas were popular, as were large lawns and flower borders. Many Edwardian gardens were designed to blend seamlessly with the surrounding architecture and often used terraces, low walls, and steps to create a sense of continuity between the indoors and outdoors. The Edwardian era’s appreciation for restrained elegance and local flora set a new standard for what a garden could be, one that was as practical as it was beautiful.

Frederick Law Olmsted: Shaping American Landscape Architecture

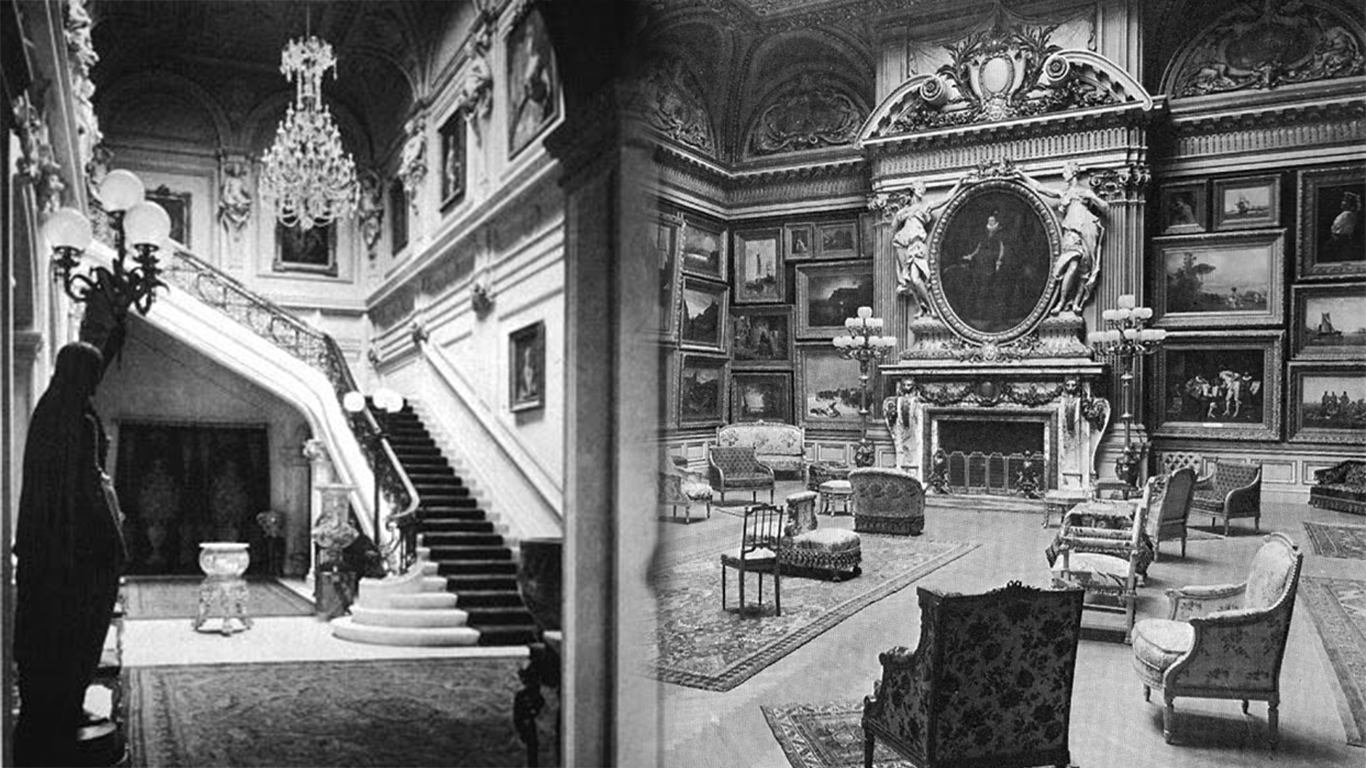

While Victorian and Edwardian landscaping styles were popular in Europe, their influence on American landscapes took on a unique character largely due to the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted. Known for designing New York City’s Central Park, Olmsted was a pioneering landscape architect who saw public parks not just as aesthetic spaces, but as essential to the health and well-being of urban populations.

Olmsted’s philosophy was grounded in the idea of nature as a restorative force. In contrast to the more rigid and ornamental Victorian gardens, he believed in creating landscapes that mimicked natural scenery and fostered an escape from the bustling urban environment. His designs were intentionally crafted to evoke a sense of tranquility, with winding pathways, open meadows, and natural water features that encouraged exploration and reflection.

Key Contributions of Frederick Law Olmsted

The Public Park Movement: Olmsted was a key figure in the public park movement, advocating for accessible green spaces in cities. His designs reflected the idea that parks should be democratic spaces, open to all people regardless of social class. This philosophy was a radical departure from the elite gardens of Europe and shaped the development of public parks across the United States.

Integration with the Natural Landscape: Olmsted’s designs emphasized the natural landscape, working with the existing topography rather than imposing rigid, geometric patterns. In Central Park, for example, Olmsted and his partner Calvert Vaux created a landscape that appears natural but is meticulously designed, using carefully placed trees, meadows, and bodies of water to create a sense of openness and peace.

The Suburban Landscape: Olmsted’s influence extended beyond city parks. He also designed residential communities that incorporated green spaces, parks, and gardens, setting the standard for suburban development in the U.S. Communities like Riverside, Illinois, were planned with curving streets, expansive green lawns, and an abundance of trees, setting the precedent for suburban landscaping that still influences American design today.

Social Reform Through Design: Olmsted saw landscape architecture as a form of social reform. His belief that green spaces could improve mental and physical health and foster community connections influenced the way cities planned public spaces. His designs for the grounds of hospitals, asylums, and schools underscored his commitment to improving lives through thoughtful design.

Olmsted’s Legacy and the Evolution of American Landscaping

Frederick Law Olmsted’s approach to landscape architecture set a new standard for American urban planning and remains influential today. His emphasis on accessible, democratic spaces laid the foundation for the American park system and inspired generations of landscape architects to consider not only aesthetics but also the broader impact of their designs on society.

The influence of Victorian and Edwardian landscaping can still be seen in Olmsted’s work, but he adapted these styles to suit American needs. While the Victorian penchant for intricate designs and exotic plants had its place, Olmsted’s designs favored open spaces, indigenous flora, and a layout that encouraged free movement and exploration. The Edwardian emphasis on harmony and simplicity can also be found in Olmsted’s work, particularly in his later projects that focused on natural beauty and ecological balance.

In essence, Olmsted’s work bridged the gap between ornamental European gardens and practical, accessible American landscapes. His legacy lives on in the many parks, gardens, and communities he designed, as well as in the principles of landscape architecture that continue to shape American cities and suburbs.

Conclusion

Victorian and Edwardian landscaping introduced a rich tapestry of design elements, from exotic plants and elaborate fountains to structured, harmonious spaces. Frederick Law Olmsted took these influences and transformed them into something uniquely American. Through his vision, American landscape architecture became a tool for social change, promoting health, well-being, and accessibility. Today, Olmsted’s influence is woven into the fabric of American cities, where public parks and thoughtfully designed outdoor spaces continue to enhance urban life. The legacy of Victorian, Edwardian, and Olmsted-inspired landscapes serves as a reminder of the transformative power of nature and design, offering refuge and beauty in an increasingly urbanized world.

Central Park, NYC designed by Olmsted.